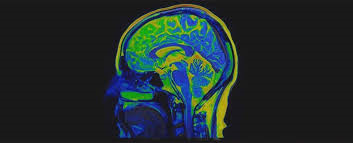

UK neurologists publish details of mildly affected or recovering Covid-19 patients with serious or potentially fatal brain conditions

Doctors may be missing signs of serious and potentially fatal brain disorders triggered by coronavirus, as they emerge in mildly affected or recovering patients, scientists have warned.

Neurologists are on Wednesday publishing details of more than 40 UK Covid-19 patients whose complications ranged from brain inflammation and delirium to nerve damage and stroke. In some cases, the neurological problem was the patient’s first and main symptom.

The cases, published in the journal Brain, revealed a rise in a life-threatening condition called acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (Adem), as the first wave of infections swept through Britain. At UCL’s Institute of Neurology, Adem cases rose from one a month before the pandemic to two or three per week in April and May. One woman, who was 59, died of the complication.

A dozen patients had inflammation of the central nervous system, 10 had brain disease with delirium or psychosis, eight had strokes and a further eight had peripheral nerve problems, mostly diagnosed as Guillain-Barré syndrome, an immune reaction that attacks the nerves and causes paralysis. It is fatal in 5% of cases.

“We’re seeing things in the way Covid-19 affects the brain that we haven’t seen before with other viruses,” said Michael Zandi, a senior author on the study and a consultant at the institute and University College London Hospitals NHS foundation trust.

“What we’ve seen with some of these Adem patients, and in other patients, is you can have severe neurology, you can be quite sick, but actually have trivial lung disease,” he added.

“Biologically, Adem has some similarities with multiple sclerosis, but it is more severe and usually happens as a one-off. Some patients are left with long-term disability, others can make a good recovery.”

The cases add to concerns over the long-term health effects of Covid-19, which have left some patients breathless and fatigued long after they have cleared the virus, and others with numbness, weakness and memory problems.

One coronavirus patient described in the paper, a 55-year-old woman with no history of psychiatric illness, began to behave oddly the day after she was discharged from hospital.

She repeatedly put her coat on and took it off again and began to hallucinate, reporting that she saw monkeys and lions in her house. She was readmitted to hospital and gradually improved on antipsychotic medication.

Another woman, aged 47, was admitted to hospital with a headache and numbness in her right hand a week after a cough and fever came on. She later became drowsy and unresponsive and required an emergency operation to remove part of her skull to relieve pressure on her swollen brain.

“We want clinicians around the world to be alert to these complications of coronavirus,” Zandi said. He urged physicians, GPs and healthcar

We workers with patients with cognitive symptoms, memory problems, fatigue, numbness, or weakness, to discuss the case with neurologists.

“The message is not to put that all down to the recovery, and the psychological aspects of recovery,” he said. “The brain does appear to be involved in this illness.”

The full range of brain disorders caused by Covid-19 may not have been picked up yet, because many patients in hospitals are too sick to examine in brain scanners or with other procedures. “What we really need now is better research to look at what’s really going on in the brain,” Zandi said.

One concern is that the virus could leave a minority of the population with subtle brain damage that only becomes apparent in years to come. This may have happened in the wake of the 1918 flu pandemic, when up to a million people appeared to develop brain disease.

“It’s a concern if some hidden epidemic could occur after Covid where you’re going to see delayed effects on the brain, because there could be subtle effects on the brain and slowly things happen over the coming years, but it’s far too early for us to judge now,” Zandi said.

“We hope, obviously, that that’s not going to happen, but when you’ve got such a big pandemic affecting such a vast proportion of the population it’s something we need to be alert to.”

David Strain, a senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, said that only a small number of patients appeared to experience serious neurological complications and that more work was needed to understand their prevalence.

“This is very important as we start to prepare post-Covid-19 rehabilitation programs,” he said. “We’ve already seen that some people with Covid-19 may need a long rehabilitation period, both physical rehabilitation such as exercise, and brain rehabilitation. We need to understand more about the impact of this infection on the brain”.

The Guardian

Lebanese Ministry of Information

Lebanese Ministry of Information