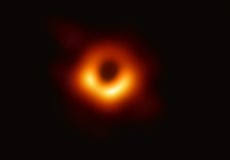

Scientists have watched a rare blast of light from a star as it was eaten by a black hole.

The unusual “tidal disruption event” was visible in telescopes across the world. It appeared as a bright flare of energy, the closest of its kind ever recorded, at just 215 million light-years away.

Such events happen when a star gets too near to a black hole, and is pulled in by its extreme gravity.

When it does, a flare of energy is unleashed that flies out into the universe, enabling the process to be spotted by distant astronomers.

“The idea of a black hole ‘sucking in’ a nearby star sounds like science fiction. But this is exactly what happens in a tidal disruption event,” said lead author Dr Matt Nicholl, a lecturer and Royal Astronomical Society research fellow at the University of Birmingham. “We were able to investigate in detail what happens when a star is eaten by such a monster.”

They were able to watch it through telescopes around the world – the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope and New Technology Telescope, the Las Cumbres Observatory global telescope network, and the Neil Gehrel’s Swift Satellite – over a period of six months, watching it as it grew brighter and then faded away.

Such a view is not usually possible because dust and debris can cover up the tidal disruption events, which are already very rare. That has made investigating the nature of the flare that is unleashed very difficult.

“When a black hole devours a star, it can launch a powerful blast of material outwards that obstructs our view,” said Samantha Oates, also at the University of Birmingham. “This happens because the energy released as the black hole eats up stellar material propels the star’s debris outwards.”

Astronomers were able to see this one, named AT2019qiz, in better detail than ever before because it was detected soon after the star was torn to shreds.

“Several sky surveys discovered emission from the new tidal disruption event very quickly after the star was ripped apart,” says Thomas Wevers, an ESO Fellow in Santiago, Chile, who was at the Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, UK, when he conducted the work. “We immediately pointed a suite of ground-based and space telescopes in that direction to see how the light was produced.”

That let them see and better understand both the flare and the debris that would usually envelop it.

For the first ever time, astronomers were able to watch the ultraviolet, optical, X-ray and radio light that came out of the event and see a direct connection between the material from the star and the bright flare thrown out as it is swallowed by the black hole.

“The observations showed that the star had roughly the same mass as our own Sun, and that it lost about half of that to the black hole, which is over a million times more massive,” said Nicholl, who is also a visiting researcher at the University of Edinburgh.

They could also watch as the cloud of debris arose and covered up the process – another unprecedented view.

“Because we caught it early, we could actually see the curtain of dust and debris being drawn up as the black hole launched a powerful outflow of material with velocities up to 10 000 km/s,” said Kate Alexander, NASA Einstein Fellow at Northwestern University in the US. “This unique ‘peek behind the curtain’ provided the first opportunity to pinpoint the origin of the obscuring material and follow in real time how it engulfs the black hole.”

The Independent

Lebanese Ministry of Information

Lebanese Ministry of Information