Study may help diagnose and identify people at risk of developing Alzheimer’s much earlier

Humans can make fresh brain cells until they are well into their 90s, but the production of new neurons falls in those with Alzheimer’s, even when the disease has recently taken hold, scientists have found.

The findings may help doctors to diagnose Alzheimer’s at an earlier stage, and identify those most at risk who may benefit from exercise and other interventions that could boost the production of new brain cells.

The work is the latest on an issue that has divided neuroscientists for decades, with some arguing humans have their full quota of brain cells by the time they reach adulthood, and others claiming fresh neurons continue to be made into old age.

In research that may help settle the matter, scientists in Spain ran a battery of tests on brain tissue donated by 13 individuals who died aged 43 to 87. All were neurologically healthy before their deaths.

María Llorens-Martín, a neuroscientist at the Autonomous University of Madrid and the senior scientist on the study, found while the healthy brains contained newborn neurons, the number declined steadily with age. Between the ages of 40 and 70, the number of fresh neurons spotted in the part of the brain studied fell from about 40,000 to 30,000 per cubic millimetre.

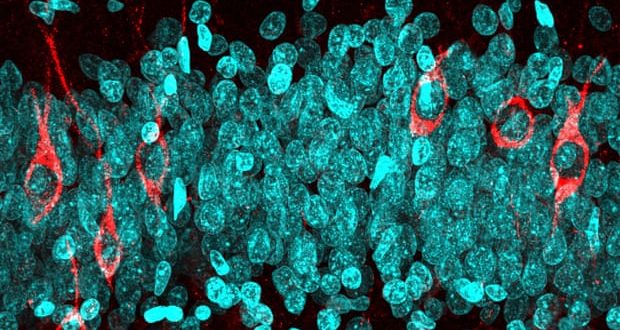

The new cells were born in the part of the brain called the dentate gyrus. It is a part of the hippocampus which plays a central role in learning, memory, mood and emotion. The gradual reduction in new brain cells appeared to go hand-in-hand with the cognitive decline that comes with old age. It suggests that in middle age about 300 fewer neurons per cubic millimetre are made in the dentate gyrus with each advancing year.

The study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, suggests that part of the reason scientists disagree on whether or not adult brains make fresh neurons is that different tests and tissue processing give different results. “In the same brains we can detect lots of immature neurons or no immature neurons depending on the processing of the tissue,” said Llorens-Martin.

Having studied healthy brain tissue, the scientists went on to look at the brains of people who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s before death. This time, the researchers analysed brain tissue from 45 patients aged 52 to 97. All had fresh brain cells in the dentate gyrus, including the 97-year old, the oldest person in which “neurogenesis” has yet been seen.

But while the Alzheimer’s patients showed evidence of new brain cell formation, there were stark differences with the healthy brains. Even in the earliest stages of the disease, their brains only had between half and three quarters as many fresh neurons as the healthy ones.

“This is very important for the Alzheimer’s disease field because the number of cells you detect in healthy subjects is always higher than the number detected in Alzheimer’s disease patients, regardless of their age,” Llorens-Martín said. “It suggests that some independent mechanism, different from physiological ageing, might drive this decreasing number of new neurons.” She said the research was only possible because of the generosity of the individuals who donated their brains to science.

She said brain scans might one day be able to detect newly-formed brain cells and so diagnose Alzheimer’s in its earliest stages. If studies on rodents are any guide, people most at risk of the disease could potentially benefit from exercise, socialising and cognitive stimulation.

Sandrine Thuret, the head of the neurogenesis and mental health laboratory at King’s College London, said the paper was “extremely timely” and provided “another strong piece of evidence that neurogenesis is occurring in the adult human hippocampus”.

Thuret said Alzheimer’s disease would not be cured by restoring neurogenesis once it had already been affected and diagnosed. But she added there was potential in using neurogenesis as a marker for Alzheimer’s before it took hold. “If you could just prevent or delay onset of cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s for a few years by maintaining neurogenesis, it would be fantastic,” she said.

She said brain scans might one day be able to detect newly-formed brain cells and so diagnose Alzheimer’s in its earliest stages. If studies on rodents are any guide, people most at risk of the disease could potentially benefit from exercise, socialising and cognitive stimulation.

Sandrine Thuret, the head of the neurogenesis and mental health laboratory at King’s College London, said the paper was “extremely timely” and provided “another strong piece of evidence that neurogenesis is occurring in the adult human hippocampus”.

Thuret said Alzheimer’s disease would not be cured by restoring neurogenesis once it had already been affected and diagnosed. But she added there was potential in using neurogenesis as a marker for Alzheimer’s before it took hold. “If you could just prevent or delay onset of cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s for a few years by maintaining neurogenesis, it would be fantastic,” she said.

The Guardian

Lebanese Ministry of Information

Lebanese Ministry of Information