First observations from Inouye telescope bring previously hazy star into sharp focus

The sun’s turbulent surface has been revealed in unprecedented detail in the first observations by the Inouye solar telescope in Hawaii.

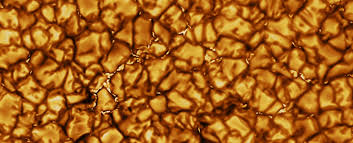

The striking images reveal a surprising level of structure hidden within the churning plasma exterior, bringing a previously hazy impression of the sun’s patchwork surface sharply into focus for the first time.

“These are the highest resolution images of the solar surface ever taken,” said Thomas Rimmele, the director of the Inouye solar telescope project. “What we previously thought looked like a bright point – one structure – is now breaking down into many smaller structures.”

The telescope’s 30km resolution is more than twice that of the next best solar observatories.

The images reveal the sun’s surface to be speckled with granular structures, like nuggets of gold, each about the size of France. Rising columns of plasma, superheated to almost 6,000C (10,800F), show up as bright spots at the centre of each grain – epicentres for the violent release of heat from the sun’s interior to its surface. As the plasma cools, it descends back below the surface via narrow, shadowy channels between neighbouring granules.

This intricate level of detail will help improve understanding of the sun’s behaviour and allow its activity cycle to be predicted more accurately.

The US National Solar Observatory’s $344m (£265m) telescope features a four-metre mirror – the world’s largest for a solar telescope – and is located at the 3,000-metre (10,000ft) summit of the Haleakalā volcano on the island of Maui.

Valentin Pillet, the director of the National Solar Observatory, described the telescope, which had been under construction since 2013, as a “formidable technological achievement”. A major challenge was maintaining the telescope’s primary mirror at ambient temperature while it looked directly at the sun – any temperature deviation causes air turbulence that could ruin the image quality. The heat is intense enough to rapidly melt metal at the mirror’s focal point.

Each night, a swimming pool’s worth of ice is emptied into eight tanks. During the day, coolant is routed through the ice tanks and distributed through the observatory by 7.5 miles (12km) of piping. More than 100 air jets are also positioned behind the main mirror.

Incoming light from the sun is deflected from the primary mirror into a chamber of mirrors that sits below the observatory’s dome. Here, the light is bounced from mirror to mirror as it is apportioned between spectrometers, polarimeters and other various other instruments. The observatory’s full suite of instruments, which will allow scientists to measure the magnetic field from the sun’s surface up to its outer atmosphere, will come online later this year.

“The bright features [in the image] … are the foothills of magnetic fields that extend all the way up into the corona and beyond,” said Rimmele. “With the additional instruments that will come online in the next six months, we will be able to measure the magnetic fields from the surface all the way up to 1.5 solar radii.”

The observations could help resolve longstanding mysteries of the sun, including the counterintuitive feature that the corona – the sun’s atmosphere – is heated to millions of degrees when its surface is only 6,000C. Understanding the physics of solar flares and coronal mass ejections could also significantly improve the ability to predict space weather, which can render GPS systems unreliable, take down power grids and knock out communication channels.

The release of the images comes as Nasa’s Parker solar probe makes observations from the edge of the sun’s atmosphere, and before the launch of the Solar Orbiter mission, a European Space Agency-Nasa collaboration, next week.

The Guardian

Lebanese Ministry of Information

Lebanese Ministry of Information